(Original Czech version of the article is HERE)

We met three times; first time some fifteen years ago, last time last week. On the first occassion, in London, this poetic lyricist, excellent songwriter and unmistakable singer Shane MacGowan (46) was at the height of his fame with his band The Pogues. A few years afterwards, he was sacked from the band because of boozing, so he started a new band, called it The Popes and in 1996 he came to play in Prague; he was on the zenith of his solo career then, and terribly drunk. On the twelfth of June [2004] he will return – he is looking forward to it a lot as he said into the telephone. He was sober, worn out, only a shadow of his past glory.

Shane MacGowan could hardly become anything else than a singer. He started his first band – The Nipple Erectors – in the punk year of 1977 and enjoyed not-a-small success with it. But his time came with a band bearing the Gaelic name Pogue Mahone. "It was a great name, we played great many gigs under it before some idiot from BBC found out that it meant Kiss my arse. So we changed our name to The Pogues. It means almost the same, but nobody minded." Apart from that, the only thing I remember from our first meeting is a homeless man who, late at night when all London pubs had long ago closed, hammered on the door of the warmly-lit pub and Shane ordered to let him in and pour him free drinks; he instinctively felt that this man was his boozing pal. In the morning I woke up on the table, surrounded with fags and spilled beer, Shane was sleeping on the floor.

I understood why so many people predicted him half a year to live at most. We didn’t see each other for a long time then, I only heard about him from time to time – Sinéad O’Connor, recently ordained as a priestess, cursed him in an interview for Reflex magazine as a damned junkie who bargains away young people to the devil. When I was interviewing Nick Cave, he had to stand from the table four times as Shane wouldn’t let him be, dialing his phone number over and over again, making the Australian songwriter call him the most annoying guy in the world.

The second time we met five years afterwards, in Prague. It was the most peculiar encounter in my life.

In 1996, Prague was finally about to host the most famous living drunkard in person; he was the star of the Jam Music Festival. But it was too late. As well as with Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin or Sex Pistols – the original line-ups fell apart sooner than communism. Instead of the legendary Pogues, Shane brought his new band – The Popes. The Pogues didn’t exist anymore; despite prophecies on Shane’s imminent end it was them who didn’t survive. They fired their singer for fear that his passion for alcohol and drugs might destroy the band – it was his task to prove that he could outlive everything, including his former band. But he resolutely refused to change himself.

A determined fan with a booklet of MacGowan’s solo debut album waited in front of the dressing room. Shane took the offered ballpoint, put it to the photograph of his own face and then tore the booklet with a violent jerk of the pen. Shreds of colourful paper fell to the ground and Shane spat on them. Then he lurched to the showers, while his manager Charlie motioned me to sit in the dressing room and wait till the Master comes back. "The interview will start in a quarter of an hour and last until Shane gives you a beating," he explained the rules laconically. My original assumption that the small room would be full of alcohol proved to be wrong. Only the fridge was overflowing with countless cans of beer and several square bottles of Jim Beam. "What will you have?" a former nurse and current Shane’s girlfriend and nurse in one person asked me. She was comfortably spread on a sofa and during the interview, she was reading Nietzsche’s Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen, in the original, of course. Finally, Shane MacGowan arrived. His walk resembled the step of a veteran sailor. He took a seat opposite me. I didn’t come empty handed – I took a one-litre bottle of becherovka [very popular Czech herb liquor] out of my bag: "This is for you." All people in the dressing room snapped to attention. "What is it?" asked the expert boozer. I briefly described the tradition and great renown of this local drink. Distrust didn’t disappear from MacGowan’s face and all people in the room started to urge him to open the bottle and try it. I chipped in: "Try it. It’s no poison." He looked me in the eye: "And why not?" He didn’t wait for an answer: "I like poison. Poison is death and death is life." Then he took a long swig and immediately spat it out. "The crap tastes like vodka with cough drops," he described the drink categorically.

Then he got angry for the first time and flung the bottle at the opposite wall; it shattered behind my back and I felt drops of fragrant herb liquor trickling down my hair. "And now to your questions, " Shane MacGowan prodded me, turned to his equally drunk manager and spluttered something which could be – with a bit of goodwill – reproduced on an out-of-tune bass guitar, but hardly with words. Charlie, however, understood him; from his answer, I grasped the assuring words that I wouldn’t "piss him off for long". "So tell him to fucking ask," urges Shane, his head turned to Charlie.

So I start asking. First of all about religion, which seeped through so many MacGowan’s songs. "Faith... God... How the fuck... Fog, thick London fog, you go through it, you cannot see a thing, your eyes are blind, you can rely only on your intuition, you clap your hands as if you wanted to catch a fly, you slowly open them and they are empty... So that’s God. Like a sand in your hands, which slips away when you open them... God is..." Charlie has been shaking with Shane for a while, the singer finally acknowledges him. "Shane, when asked about faith and God, reply: Yes, I believe!"

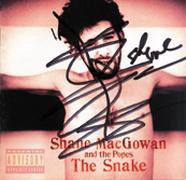

So a different tactics. I try asking why the American actor Johnny Depp appeared as a guest guitarist at The Snake album. I get a half-answer: "I don’t understand the fucking question. Johnny is a good bloke, I like him. He can play with us, why couldn’t he? He likes us and we like him." Even the next attempt is fruitless; I try to find out why MacGowan’s new band is called The Popes, which is phonetically so close to the original The Pogues. "Isn’t it a great name? It is, it’s really great. It was my idea. I like it. We’re not holy, but who the fuck is? The pope? He isn’t any holier than we. It’s fucking truth, he isn’t any better!" Things went on like that for about half an hour. Finally, I thanked him for the talk which was as close to an interview as MacGowan was to sobriety, and I asked him to sign the album for me. The famous drunkard took a felt-tip pen and with the meticulousness of a dyslexic very slowly wrote his Christian name; it totally exhausted him, so instead of adding his surname, he scrawled the sleeve of the album over with a meaningless scribble. When I was leaving, I was sure that we would never see each other again. I gave him half a year of life at most. For a long time nothing happened, Shane MacGowan just released two albums, rather average than good. His fame started to fade away. And then he decided to come to Prague again and a week before the gig I got his telephone number. This time he answered in whole sentences that even made sense. For example when he said that he was looking forward to coming to Prague, where he would perform for the first time in his life. But it somehow lacked spice. The whole talk reminded me of the two Pogues albums released after MacGowan’s departure – nice songs, but something was lacking. They were too sober. Suddenly I missed the drunk ramblings. It’s somehow a part of Shane MacGowan. Even if it should mean that he has the last half a year of his life before him.

Photos: Profimedia.cz / Corbis

English translation © Zuzana

Original location of the Czech article:

http://www.reflex.cz/Clanek16599.html